Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church by Hans Boersma Baker Academic Press 336 pp. March 2017

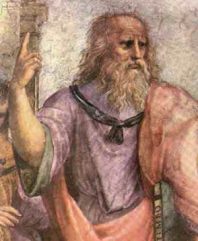

Several years ago, before the Lord blessed us with ridiculously time consuming and needy children, my wife and I got the chance to visit Italy and see some of the great art of the West. After a very strenuous day of exploring Rome and Vatican City, as we were finishing up our Vatican Museum tour, our guide asked if any of us wanted to walk a bit farther to go to the Papal chambers where Raphael’s School of Athens was painted. It was a bit of a walk though, she said, and so we could skip it if we wanted. All I wanted to do was sit down and eat some gelato, but I didn’t know if I would ever get the chance again and prayed to the good Lord to give my legs one more mile. He did and I saw Raphael’s painting, which, as any lover of the humanities knows, is a real treasure. It’s also a great way to envision Hans Boersma’s thesis in his new book: we have all fallen far too hard for Aristotle as moderns, and to recover a proper biblical hermeneutic, we need to turn back to Plato.

Though this comparison is somewhat crude, I don’t think it’s too far off. The focus of Raphael’s painting, as you know, is the competing metaphysic between Plato and Aristotle: between Plato’s mysticism—he’s the one on the left pointing up to the mysteries of the heavens— and Aristotle’s embodied realism—Aristotle holds his hand down to the earth embodying his focus on concrete scientia. Like Raphael’s painting, Boersma’s book also revolves around this dualistic metaphysic; he believes that Plato and Aristotle represent the two competing methods of Scriptural interpretation. Scripture as Real Presence is an exercise in patristic exegesis because we need to get back to the way the fathers read Scripture. In short, the fathers read Scripture better than we do because they had the right metaphysics. As pre-moderns, the church fathers were Platonists, combing the Scriptures sacramentally (Boersma’s term), looking for Christ in every sentence and every verse.

Though this comparison is somewhat crude, I don’t think it’s too far off. The focus of Raphael’s painting, as you know, is the competing metaphysic between Plato and Aristotle: between Plato’s mysticism—he’s the one on the left pointing up to the mysteries of the heavens— and Aristotle’s embodied realism—Aristotle holds his hand down to the earth embodying his focus on concrete scientia. Like Raphael’s painting, Boersma’s book also revolves around this dualistic metaphysic; he believes that Plato and Aristotle represent the two competing methods of Scriptural interpretation. Scripture as Real Presence is an exercise in patristic exegesis because we need to get back to the way the fathers read Scripture. In short, the fathers read Scripture better than we do because they had the right metaphysics. As pre-moderns, the church fathers were Platonists, combing the Scriptures sacramentally (Boersma’s term), looking for Christ in every sentence and every verse.

As moderns, we have forfeited our deep reading of Scripture for a historical, scientific hermeneutic—a hermeneutic in line with Aristotle’s metaphysic—content to stay on the surface of things, content to squalor in the mud and the bugs—when we could reach to the heavens with Plato. That is the thesis of the book. Let me now fill out—and question—that picture.

Boersma’s book is driven by two main contentions: first, to get us to see that we must have a sacramental metaphysic in order to properly read Scripture. Second, and inseparably related with the first, to convince the reader to reclaim the Church Father’s sacramental reading of Scripture. Let’s take both in turn, beginning with the second claim:

As anyone familiar with Hans Boersma’s thought will know, he is a sacramental theologian. It will be no surprise, then, to find the thesis that we must read Scripture sacramentally at the heart of his new book. As for his understanding of all creation as sacrament—that all things point to the goodness and reality of God— absolutely: understanding Thomas’ analogia entis—that we are all gifted being at every moment of our existence—was a defining moment in my intellectual life and spiritual understanding. Unfortunately, Boersma’s usage of the term “sacrament” is confusing in this book. When he turns to a “sacramental hermeneutic”, or the reading of Scripture he believes the Church Fathers employed, the term suddenly transitions from seeing all things as revealing God to seeing all Scriptures as revealing Christ. The usage is imprecise and leads to misunderstandings. Why not call it a “Christocentric” understanding of Scripture, for example? The reason I bring it up here is because I am not convinced of everything that he believes a “sacramental hermeneutic” entails and yet I would very much want to affirm Boersma’s sacramental theology. Let me draw this out by going to Boersma’s second driving theme.

The most fascinating, though controversial, motif of Scripture as Real Presence is Boersma’s thesis that we read Scripture only as well as our background metaphysics allows us to. Drawing from Origen, Boersma says that, “good metaphysics leads to good hermeneutics” (5). What that means more concretely is, “The way we think about the relationship between God and the world is immediately tied up with the way we read Scripture” (ibid). As moderns, we look at Scripture much too mechanistically, which, Boersma believes, has led to reductionism—the stripping away of profound truths and formation from Scripture. Instead of reading as moderns, we must get back to the pre-modern (read Platonic) “sacramental hermeneutic” of patristic interpretation. Boersma explains: “the reason the church fathers practice typology, allegory, and so on is that they were convinced that the reality of the Christ event was already present (sacramentally) within the history described within the Old Testament narrative. To speak of a sacramental hermeneutic, therefore, is to allude to the recognition of the real presence of the new Christ-reality hidden within the outward sacrament of the biblical text” (12).

His usage of sacramental is unclear to me here—is it because Christ is the Logos through which all of creation and reason is informed that He is present in all parts of the Old Testament narrative, for example? What’s concerning to me is how Boersma next marries a “sacramental hermeneutic” to Christian Platonisim: “To speak, therefore, of a ‘sacramental hermeneutic’ is not to reject other, perhaps more common labels [like allegory, anagogy] but rather to allude to the shared metaphysical grounding of these various exegetical approaches” (13). So, wait…. Does that mean I can’t read Scripture Christo-centrically if I’m not a Platonist? It often seems like it. Consider this:

“My Christian Platonist convictions imply that I will happily go back to the church fathers (or the Middle Ages or anywhere else) to look for insights that can contribute to the practice of a sacramental reading today. After all, the question of whether a ressourcement of the exegesis of the church fathers is possible and worthwhile is, ultimately, a question of the truth or false of its metaphysical and hermeneutical presuppositions (276).”

The way this works out in practice is that Boersma takes on the popularity of N.T. Wright whom he has stand in for the “redemptive historical” method of biblical interpretation and the new perspective on Paul.

The redemptive historical method Boersma sees as too confined by a modern hermeneutic. He says, “One of the greatest pastoral drawbacks of both the historical method and the new perspective on Paul is that it’s hard to see how, with these approaches, readers of the Old Testament are able to relate the historical narrative to their own lives” (xiv).

Additionally, “The weakness of historical exegesis…is that it doesn’t treat the Old Testament as a sacrament that already contains the New Testament reality of Christ” (xv).

In other words, without a Platonic metaphysic that allows for allegorical readings, the reader of the biblical text is unable to see how all of Scripture points to Christ and the Old Testament stands relevant only inasmuch as we can leave it behind and relate it to today. I found this an odd claim given how much I have benefited from seeing both the Old and New Testament scriptures in their historical context as a grand narrative with Jesus at their center and as their climax: in other words, in the redemptive-historical method that Boersma wants us to reconsider. In fact, I see Boersma’s dichotomy between historical and sacramental exegesis to be the biggest weakness with this work. I don’t think that he would advocate abandoning historical exegesis but in certain places he certainly discounts its importance and its relevance. In the conclusion, for instance, after ringing an optimistic tune about whether a return to pre-modern patristic exegesis is possible, Boersma says, “Thankfully, it is possible to point to a growing conviction, not only among dogmatic theologians but also among biblical scholars, that exegesis is not primarily a historical endeavor and that it first of all asks about the subject of the text—that is to say, about God and our relationship to Him” (277, emphasis added).

Now, Boersma would simply accuse me of being too wedded to my modern metaphysic but a statement like that makes me profoundly nervous. Chrysostom, Boersma says, expressed his concern that an allegorical reading of the Scriptures could lead to the text saying whatever the reader wanted them to. But we should not fear, Boersma says, because the “rule of faith” disallows any reading of Scripture that would conflict with orthodoxy. But what of the myriad of conflicting interpretations that lead daily to denominational splits, all “read in the Spirit”? Chrysostom’s worry becomes my fear when I read a sentence that states that exegesis isn’t really about history. Does this not imply that we should simply throw the author’s original intent out the window? Indeed, scriptural interpretation is not only history but it is certainly not less. I understand that we stay wedded only to the literal sense of Scripture at our peril and spiritual impoverishment, but to imply that we do not begin with the history and context of Scripture—that Scripture is not primarily about what the author’s intended to convey—invites, unfortunately, not a pre-modern sacramental reading contained within the Church’s rule of faith, but only encourages the continual splintering of the tens of thousands of denominations that we see today.

Boersma, as a self identified Christian Platonist, has written an important book in which he challenges the dominance of modern historical exegesis in favor of a pre-modern “sacramental hermeneutic” which follows in the footsteps of the Church fathers. We should stand and applaud Boersma’s sacramental theology and his desire to read Scripture more richly. All of creation and Scripture is a sacrament in that it points to the presence and glory of God and Boersma is one of our finest Protestant voices in reminding us of that fact. But I question the wisdom of downplaying historical exegesis for a Platonic and allegorizing hermeneutic. (In fact, I quite like Aristotle.) In my experience, 21st century Protestant readers of Scripture are already far too uprooted from the important details of, say, second-temple Judaism, in order to make their reading of Scripture more meaningful and fruitful. Surely we can see Christ in all of Scripture without being Christian Platonists. I’m tired of being asked, “What is this Scripture saying to you?” What I want to know is: what did the writers intend to say to their original historical audience? Then, and only then, may I ask and answer the subjective question with conviction.

*Thanks to Baker Academic for the review copy.

Thanks very much for a helpful review and critique, Mark. I’ve just become acquainted with the Theologian’s Library, and was glad to find you. Exciting stuff 🙂

I have one question: As you consider your claim that myriad of interpretations leading to doctrinal splits are connected to people thinking that they are reading “in the Spirit,” can you expand on how you would explain the same phenomenon amongst those in the modern historical exegetical school? Said another way, if you’re suggesting (and I don’t want to pin that on you yet—it’s not totally clear to me) that those who do not ground themselves in historical exegesis are contributing to denominational splitting, in what way are the myriad of interpretations that come from modern historical exegesis contributing to those same splits? Is it not just as easy to argue that interpretive pluralism is just as widespread among scholarly, historically-oriented exegetes?

Thanks again! Great critique and review.

LikeLike