Note: This is the first part of a planned 15 part series on the power of fiction. We believe here at the Theologian’s Library that fiction should be read along with theology, philosophy, and all the rest. Fiction has the power to put oneself into the mind and shoes of other people which is a particularly valuable skill for the pastor and cultural interpreter. We hope to give you a solid recommended list of fiction that will improve your preaching and teaching, your understanding of the human condition, and deepen your love of Jesus.

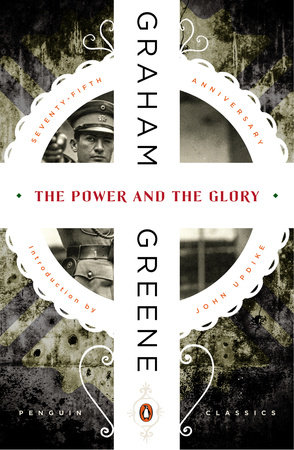

Haunting, apocalyptic and desolate are the three obligatory superlatives that come to mind in thinking over Greene’s masterpiece in its 75th birthday and the mood that Greene creates in its 200-something pages. Time has the novel on its “Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century List” and for good reason. It contains a weight, a gravitas, that is hard to come by in fiction today. Greene’s Catholic faith is well-documented but it is worth reiterating that without it, there is no masterpiece, no Power and the Glory. Take that Christopher Hitches and your “religion poisons everything” the subtitle to his 2007 book, God is Not Great. (By the way, I do miss you Mr. Hitchens. In fact, I should see what you had to say about Greene, I always do value your input on literature, if not so much on questions of faith.) In his forward to the edition that I read, John Updike says that The Power and the Glory is the first novel in which Green’s Catholicism doesn’t feel “tacked on” and somewhat superfluous. Indeed, the specter of genuine faith in the midst of starvation, ruination and hopelessness is what makes Greene’s dodranscentennial novel (75th birthday) a masterpiece.

During the reading of The Power and the Glory, I googled (yes, it is in the OED, I have just learned) “Graham Greene / Cormac McCarthy” because, having come to McCarthy first, I was struck with the similar apocalyptic-like tones of both of these writers. Sure enough, Penguin publishing has written in the 75th anniversary edition that Graham’s novel traces its history “back to Dostoyevsky and forward to McCarthy.” The Dostoyevsky comparison is obvious because of the very real, yet grotesque, suffering of the “whiskey priest,” the nameless main character of the novel.

Just a quick side note, having just read Vanhoozer’s Pastor as Public Theologian and traveling to Chicago to hear him at the “Pastor as Public Theologian Conference”, I was surprised that he didn’t list Greene and his “whiskey priest” (the anonymous main character of the novel) as an example of men of the cloth in his survey of popular portrayals of pastors and the negative effect those usually have on religion. Regardless, I appreciated Vanhoozer’s section on the power of fiction and why ministers need to be reading fiction in order to preach more powerfully and to understand the human condition more deeply. If you are looking to be persuaded that fiction is indeed, important, I would recommend picking his book up.

A little autobiography before I get to the book itself: My only contact with Greene before reading this work was reading his Quiet American (1955) for senior honors English back in the day. I remember writing a paper contrasting the protagonist (Alden Pyle) with —with whom…— Hamlet perhaps? I would love to find that paper and read it. I’m sure it would make me cringe, but many of my writings do that, like I’m sure they do for you as well. It’s like hearing your voice played back to you, no one likes that!

I remember writing that paper in the late evening hours at Homer’s Coffeehouse on 91st and Metcalf in the Kansas City suburbs. It was one of the first times that I realized I thoroughly enjoyed literary criticism and the power of words to speak into the painful realities of everyday life. I remember feeling drawn out of myself —what a tremendous experience!— and catching a glimpse of the world around me, a glimpse that is so hard to grab in the teenage years (and many never grasp it). Renaissance humanists understood this power, the dunamis of literature to make the present make sense, the power of words written centuries ago to transform this very second. They called it bonae litterae. So Greene was powerful in my early formation and my senior English teacher was as well, giving me the space to discover what those Renaissance rascals meant by that beautiful Latin phrase. I have since reconnected with him in order to tell him so. (I am a bit ashamed to admit it now, maybe I shouldn’t be I don’t know, but it was reading Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg per his recommendation that sent me off on my love of the written word and my love of books in young adulthood. For that, I am eternally grateful.)

To the book itself.

A way in to this masterpiece for those unfamiliar comes from the pixels of a recent, but already of classic-status television show. Lovers of Vince Gilligan’s “Breaking Bad” will undoubtedly devour The Power and the Glory; there are so many parallels, so many similar scenes. Greene’s novel is set in the heat, desolation and atheism of a 20th century Mexico stripped of its faith by a quasi-communist government (the “red shirts”.) Walter White’s life is set in the emptiness, desolation and meaninglessness of 21st century New Mexico. From the beginning, though, the whiskey priest’s situation looks much more existentially dire than Walter’s. Walter, in the beginning, though confronted with a cancer diagnosis still has a loving family and seemingly stable emotional well to draw from, but his life quickly descends into chaos and both men are forced by circumstances outside of their control to confront their past, and ask how and why both have become who they are and if they care to stay that way. Walter’s search leads him to create an alter-ego complete with piles of cash, sunglasses and that ridiculous hat to his ignominious end (in the eyes of this writer to be sure). The whiskey priest is lead back into the clutches of the lieutenant who has been hunting him like an animal by the plea of a dying renegade for last rights, knowing that it will signal his martyrdom but unable to evade his “duty” as he refers to it.

One of the most powerful questions posed by Walter and the whiskey priest and why both works of art will be talked about for years to come is, who is a person, really? And what happens when the person that once was becomes so radically different from his past that he becomes unrecognizable? Was he ever that person, or were those years simply an apparition of extended fabrication? That’s the question that the whiskey priest is forced to ask himself over and over in the novel and the answer, he knows, means life or death. Christianity has been outlawed and so to admit that he, indeed, is a priest and to live that out will be at one and the same time, to find his life and lose it. Therein lies the pull of the novel. Is the whiskey priest more alive when he is living up to his vocation as a minister of God, even though it may end his life, or should he scrap all of that now in order to survive? The priest wrestles with whether his life is even worth preserving. Is he is doing greater harm to those he comes into contact with as an affront to the idea of God? If this is a man who has represents God, then what do we want with that God? the priest imagines people will say. Hiding out in one of the villages the priest asks himself,

If he left them, they would be safe, and they would be free from his example. He was the only priest the children could remember; it was from him they would take their ideas of faith. But it was from him too they took God – in their mouths. When he was gone it would be as if God in all this space between the sea and the mountains ceased to exist. Wasn’t it his duty to stay, even if they despised him, even if they were murdered for his sake? even if they were corrupted by his example? He was shaken with the enormity of the problem (65).

The authorities have taken to shooting a hostage in every village until the whiskey priest turns himself in. The constant tension between turning himself in as the last hold out priest to save the lives of innocents and continuing to run to preserve his own life and to do the work of God is what gives the novel its immediacy, it’s what turns it into bonae litterae. The whiskey priest knows that he is not a good priest, but he is all that’s left. The bursting of this almost unbearable weight comes, not when the priest has decided to give himself up in order to administer last rights to the dying fugitive, but in his conversation with the lieutenant after he has been arrested.

“You have such odd ideas, the lieutenant complained. He said, ‘Sometimes I feel you’re just trying to talk me round.’

‘Round to what?’

‘Oh, to letting you escape perhaps – or to believing in the Holy Catholic Church, the communion of saints…how does that stuff go?’

The forgiveness of sins.’

‘You don’t believe much in that, do you?’

‘Oh yes, I believe,’ the little man said obstinately” (206).

And so there it is. The priest does truly have faith. He has not been running away simply to survive. He does believe that he is the hands and feet of Christ, that the host does turn in to the body and blood of Jesus and that confession will save people from eternal separation. And so we, the readers, also continue to believe. The little priest has given us his permission. And his life.

-Mark